SHRIMPONICS is a collaborative, ongoing project by Alex Bernstein and Brandan Griffin. Check this page for periodic updates.

The text of SHRIMPONICS was composed in an email thread over the course of several months. It grew out of video meetings in which we discussed a poetics based on biology, non-human experience, and labor. In our writing, we came to focus on two figures: the shrimp and the mound of sugar. The shrimp was chosen by Griffin because of his interest in arthropod anatomy and the shrimp's traditionally humble relation to humans. The mound of sugar is a particular fascination of Bernstein's due to a passage in Deleuze's Bergsonism, which excavates the experience of a mound of sugar.

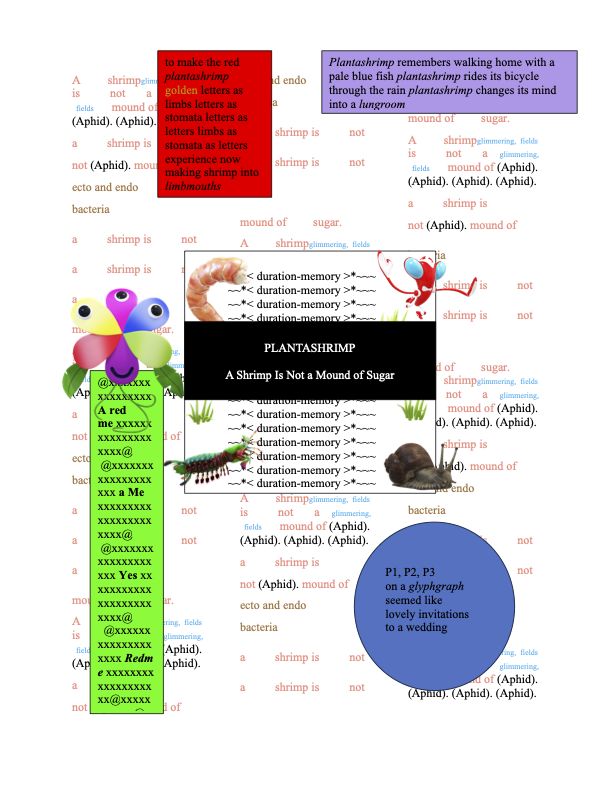

In turn, this text is in the continuing process of being cultivated into a visually and typographically oriented document, one that is capable of re-formatting the attention of the human reader into shrimp- or sugar-experience. Our only (loose) constraint in developing this document is that it should use the tools and features native to Microsoft Word to create its effects. As a result, anybody (in theory) could produce their own version of a SHRIMPONICS document. Its formalism is to be read as a series of gestures anyone could engage in, as if the doc's movements are as much the reader's as they are the writers'.

SHRIMPONICS is also about finding a way to create something new within the psychologically bludgeoning conditions of labor, if only by inventing more time. We hope others may be inspired to reclaim time in their own ways and with equally speculative ambitions.

The second SHRIMPONICS document acts as a further crystallization of some of the aesthetic ideas explored in our discussions and SHRIMPONICS 1.

Bernstein's writing on the shrimp's gestalt in Tank Temporality condenses a great deal of thinking about non-human cognition into a shrimpified Lacanian text. In a psycho-algorithmic twist, Bernstein also discovered that his phone was constantly feeding him shrimp-related content—it had been listening to him talking effusively about SHRIMPONICS in real life. We must not thank the phone; at the same time, we must not ignore the material realities the world feeds us; Bernstein screencapped the shrimp posts. Overlaid on the shrimp-grid is a short text by Griffin about poetry's function as a model of a world.

This document includes a sequence by Griffin, crystall(histori)ography, in which Griffin assembles various found-perspectives into the molecular structure of sugar. We must reassemble the human as the non-human. What terrible histories had to crystallize to give rise to refined sugar? To the cell? To the shrimp tank?

Of the first page of SHRIMPONICS 3, Bernstein writes:

~~> In Decoder Pod / Decapoda, I try to find a method for articulating adaptive, biological activity that can't be detected by human observation, the flustering, morphological activities of generating and maintaining a body, and I also attempt to make fun of the all-too-serious scientific method that continues to disregard, in very obvious ways, the fundamental gaps in human observation when it comes to verifying the experiences and lives of nonhuman actors. The study I used as context, "Genome Sequencing and Assembly Strategies and a Comparative Analysis of the Genomic Characteristics in Penaeid Shrimp" (2021), arises from the fact that penaeid shrimp are the main group of exported species that account for 16% of the total value of internationally traded fishery production, year after year, just less than that of salmon and trout (18%). The (s)quid pro quo of human consumption and attraction drives this research, whereas I think a poetics can better visualize the experience, labor, and lifecycles of shrimp. If anyone feels confused, imagine how shrimp must feel!

~~> At the same time, a genome generates biomass by reading and acting on inheritance. What makes shrimp a novel species is their tendency toward repetition and duplication. They have many difficulties in forming a stable biology because they are prone to mutations. Decoder Pod / Decapoda plays with these mutations through homophonic changes in word, sounds, and syntax while imaging the size of the shrimp's genome. On the left side, one text describes figuratively the experience of being a shrimp in the water, and on the right side, that text appears mutated, but the line sounds the same, hugging a locus of breath and music that echoes the left. In the background is a graph that surveys the sizes of seven decapod genomes, noting the quantity of material that goes into generating a shrimp's body. The entire thing mimics a shrimp's perspective, as it is farmed in the tank.

The middle pages of SHRIMPONICS 3, written by Griffin, use text generated by different loosely procedural modifications of the description of a lump of sugar in Gilles Deleuze's text Bergsonism. These pages are meant to burrow down to a microscopic, metabolic level of the shrimp. Living things (and, by extension, organic temporality) are powered by sugar.

The document ends with a watermark text, a marine ecology of layered writing that rejects all jurisdictions and seals of corporation.